/Excerpt from an article written by Vanaajamaja instructor Andres Uus and published in TIMBER FRAMING. Journal of Timber Framers Guild. No 107, March 2013/

Historians believe that the first log buildings (ristpalkmaja) in the Estonian region were built at least 2000 years ago and presume that Estonians learned their building skills from the Baltic tribes; the Estonian words for axe (kirves) and wall (sein) originate in Baltic languages rather than in the dominant Finno-Ugric. In vernacular peasant architecture, both dwelling houses and outbuildings typically were built of round logs until the middle of the 19th century, while hewn logs were used for manors and public houses. Axes were the sole tools employed in the construction of log buildings until the 1860s, when crosscut saws won a place in the carpenter’s toolkit.

Norway spruce (Picea abies) and Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris), both indigenous to Estonia, were the traditional species of choice for log builders, a preference that continues today. Historically, woodsmen cut and brought timbers to the jobsite in midwinter during the old moon (December to February), peeled and stored them for spring, and the building was cut and raised during the same summer.

Foundations were generally primitive, with walls supported by piers of quarried stone, infilled with loose stone, rubble, clay or sand. Often outbuilding foundations were not infilled at all. After the second part of the 19th century, lime mortar use became widespread even in rural areas, and henceforth the quality of the foundations increased and the lifespan of the buildings lengthened. Birch bark served as a barrier against damp between the first log and the stone foundation.

Dowels or keys placed at intervals along the logs helped bind larger walls. To keep walls in plane at door and window openings, plank jambs (tender) were grooved into log ends at the openings. Side jambs typically cut 5 percent short allowed wall logs to shrink and settle.

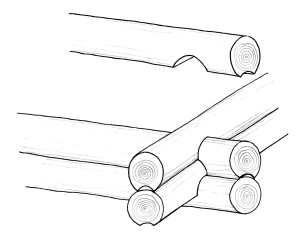

Log diameters varied with building type. For houses and barns it was generally 7 to 10 in. In the traditional full-scribe procedure, not always used today, the corner joint (neck) was scribed first and then, once the logs were in proximity, the bottom of the upper log was grooved and scribed to fit the lower.

Koerakaelatapp

Joinery Estonian carpenters employed a wide range of lapping joints to bind the corners of their buildings. Though the topic warrants fuller treatment, here we show the most nearly typical corner joints, in order of historical development. (Nurk means corner, tapp means notch.) With widespread use of the crosscut saw in the mid-19th century, the järsknurk (“steep corner”) joint, faster to build, became the most popular for buildings with log walls exposed to the exterior. In the town milieu, and in rural areas beginning in the 20th century, the kalasabatapp (“fishtail notch”) became the preferred corner joint (puhasnurk). This notch was generally used for logs hewn flat on their vertical faces, to accept sheathing or plaster; it was more rarely used on round-log buildings, with logs hewn flat near their ends to allow for a clean joint.